Declaration

of Human Rights; 1798-version

(see

also in detail the

V.N.-version

).

Charter

of Order

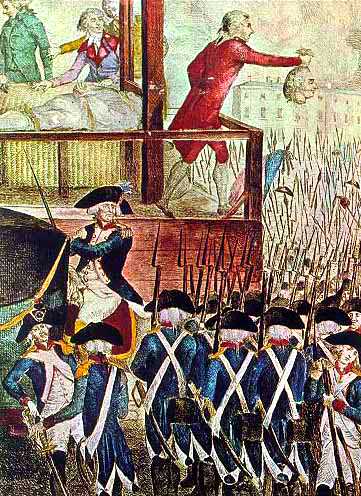

The

Declaration of Human Rights of 1789 founded the

freedom of the French after the revolution to

the example of the declaration of independence

in America. With this revolution influenced by

the ideas of the philosopher Jean-Jacques

Rousseau (1712-1778) came it in France

nationally and internationally, to opposition

with the philosophy of Enlightenment of the

centuries before in which gradually religion and

science had drifted apart. It was now science

itself that philosophically got divided. It was

no longer a gentleman's discussion between

empiricists and rationalists about the value of

inductive - from the specific to the general; -

and deductive - from the general to the specific

- reasoning; it became a political struggle

between liberals and conservatives. With

Rousseau, himself an emotionally challenged

person of the common people, was civilization

from then on not right away considered good or

elevated, but on the contrary bad; the emotional

was the good of nature and was superior to

reason; and the interest of the individual was

subordinate to that of the group. The

sovereignty of reason which would not so much

accept the lead of the sensual as the lead of

the - possibly not provable - moral principle,

was, also following empirical philosophy of

eighteenth century England, called in question

as being a source of knowledge and subjected to

a system of political, democratic control from

without. The man of nature had to prevail over

man of culture, feeling had to prevbail over the

mind. The conflict between empirical feeling en

rational understanding, arising from the

philosophy

of Enlightenment, materialized with the

impurities of the philosopher's ego in that

Revolution. In christian reform reached

Enlightenment a deadlock, being ignorant and

thus in fact unenlightened about what factually

the concern of authority was, who would have the

last word with the plea for the individual

person heard since the fall of catholic Rome.

Christian Reform, in countering the religious

and noble ego, only resulted in more ego. In

fact could the ego of societal classes and

status groups - which indian-style taken

together could be called castes - not arrive at

purification in the Enlightenment, that indeed

did justice to the truth of the individual, but

couldn't find any liberation in a commonly felt

respect for the person. The classical ideal of

an integrity of thought and feeling in one

universal science, in one historically founded

classical order, was lost fighting about

political power. Rationality and religiosity not

of love for nature, the way Rousseau put it,

turned out to be nothing but treason to human

nature. That passion, that maybe positively

aggressive and uncontrolled nature of what he

called the 'noble savage' is the honesty

that should liberate thus was the creed of the

Revolutionary 'Enlightenment' that opposed the

failed elitist 'Enlightenment'. In fact was the

liberal philosophy of the revolutionaries the

manifestation of the concept of enlightenment

that itself therewith found its demise. The fray

of the ego of the philosophers in that idea of

enlightenment, that notion of a separated,

individualized and emancipated self, could find

no freedom from fear and misery in service to

the ideal. From the philosophy of reason one had

landed in a philosophy of rationalistic

repression and self-righteousness. Together with

the philosophers Voltaire and Diderot arose, as

the upbeat to the later twentieth century

horrors - that in the form of world wars would

manifest themselves as the backlash of colonial

violence - a willingness for violence because

that would be the only way to counter and

overturn the cramped falsehood and

possessiveness of especially the clergy and the

nobles exploiting being a burden to the citizen

(or the colonial subject or slave). With the

revolutionary liberalism which, notwithstanding

nineteenth century romantic and puritan efforts

to restore the classical order, freaked out a

century later in communism and fascism, then

smothered in the blood of the ignorant citizens

the last bit of philosophical pride and

self-esteem of the westerner who, at the

beginning of the twenty-first century is at a

loss with the ever lingering opposition of, this

time, the fundamentalists. For the struggle of

the classes continues as long as those classes

due to the absence of a philosophy of

association try to subdue or exclude one

another. philosophy

of Enlightenment, materialized with the

impurities of the philosopher's ego in that

Revolution. In christian reform reached

Enlightenment a deadlock, being ignorant and

thus in fact unenlightened about what factually

the concern of authority was, who would have the

last word with the plea for the individual

person heard since the fall of catholic Rome.

Christian Reform, in countering the religious

and noble ego, only resulted in more ego. In

fact could the ego of societal classes and

status groups - which indian-style taken

together could be called castes - not arrive at

purification in the Enlightenment, that indeed

did justice to the truth of the individual, but

couldn't find any liberation in a commonly felt

respect for the person. The classical ideal of

an integrity of thought and feeling in one

universal science, in one historically founded

classical order, was lost fighting about

political power. Rationality and religiosity not

of love for nature, the way Rousseau put it,

turned out to be nothing but treason to human

nature. That passion, that maybe positively

aggressive and uncontrolled nature of what he

called the 'noble savage' is the honesty

that should liberate thus was the creed of the

Revolutionary 'Enlightenment' that opposed the

failed elitist 'Enlightenment'. In fact was the

liberal philosophy of the revolutionaries the

manifestation of the concept of enlightenment

that itself therewith found its demise. The fray

of the ego of the philosophers in that idea of

enlightenment, that notion of a separated,

individualized and emancipated self, could find

no freedom from fear and misery in service to

the ideal. From the philosophy of reason one had

landed in a philosophy of rationalistic

repression and self-righteousness. Together with

the philosophers Voltaire and Diderot arose, as

the upbeat to the later twentieth century

horrors - that in the form of world wars would

manifest themselves as the backlash of colonial

violence - a willingness for violence because

that would be the only way to counter and

overturn the cramped falsehood and

possessiveness of especially the clergy and the

nobles exploiting being a burden to the citizen

(or the colonial subject or slave). With the

revolutionary liberalism which, notwithstanding

nineteenth century romantic and puritan efforts

to restore the classical order, freaked out a

century later in communism and fascism, then

smothered in the blood of the ignorant citizens

the last bit of philosophical pride and

self-esteem of the westerner who, at the

beginning of the twenty-first century is at a

loss with the ever lingering opposition of, this

time, the fundamentalists. For the struggle of

the classes continues as long as those classes

due to the absence of a philosophy of

association try to subdue or exclude one

another.

The

drama of western philosophy is that with all the

manslaughter of the citizen missing a good lead

the philosophers each for themselves are still

quite right; of course must reason prevail,

experience be decisive and must we become

brothers without the falsehood of a culture

going against nature. Naturally, but what for

God is the integrity of this philosophy, what is

the place of all these separate ideas in one

coherent culture? Christianity fell short with

itself, more was needed, at least more respect

for other cultures that, so was discovered with

imported china from the Far East and such,

possibly also could be offering something. The

Germans I.

Kant

(1724-1804) and A. Schopenhauer (1788-1860) were

of no insignificant contribution in the

nineteenth century to put the dualistic strife

to an end and arrive at a better cultural

integration. But in de end proved I.

Kant, the philosopher of dualism, noumenal (to the

spirit) be it phenomenal (to the phenomenon),

not capable of proper reference and turned

Schopenhauer, who was capable, out not to be

able to attach much belief to the authority of

that reference, found in eastern philosophy. He

indeed connected the eastern with the western of

philosophy, but remained spiritually impure in

the dark with his disbelief in a controlling

personal Godhead. He verily, as it should,

discriminated between an A and an A, two

identical variables that nevertheless differ in

time and space, but was with the free from

illusion identifying of the phenomenal with the

noumenal of the philosophy of I. Kant that he

wanted to perfect and complete, just like

Baruch

Spinoza

(1632-1677) with his denial of the miraculous

caught in the impersonal, which, with the denial

of the cyclic and balanced of the person,

inevitably leads to chaos. And so arose in the

nineteenth century the further breaking up of

science in the analytical schools and esoteric

schools of psychology and theosophy that more

doctrinaire than philosophical emphasized a

self-realization which also couldn't get beyond

the still more in books condensed ego of the

antroposophical purple underwear that had to be

rejected by the Indian guru J. Krishnamurti

(1895-1986) and the finite cigar in the mouth of

S.

Freud

(1856-1939) which cost him his health.

the philosopher of dualism, noumenal (to the

spirit) be it phenomenal (to the phenomenon),

not capable of proper reference and turned

Schopenhauer, who was capable, out not to be

able to attach much belief to the authority of

that reference, found in eastern philosophy. He

indeed connected the eastern with the western of

philosophy, but remained spiritually impure in

the dark with his disbelief in a controlling

personal Godhead. He verily, as it should,

discriminated between an A and an A, two

identical variables that nevertheless differ in

time and space, but was with the free from

illusion identifying of the phenomenal with the

noumenal of the philosophy of I. Kant that he

wanted to perfect and complete, just like

Baruch

Spinoza

(1632-1677) with his denial of the miraculous

caught in the impersonal, which, with the denial

of the cyclic and balanced of the person,

inevitably leads to chaos. And so arose in the

nineteenth century the further breaking up of

science in the analytical schools and esoteric

schools of psychology and theosophy that more

doctrinaire than philosophical emphasized a

self-realization which also couldn't get beyond

the still more in books condensed ego of the

antroposophical purple underwear that had to be

rejected by the Indian guru J. Krishnamurti

(1895-1986) and the finite cigar in the mouth of

S.

Freud

(1856-1939) which cost him his health.

The

philosophy, gradually repressed by political and

therapeutic practices of problem-solving, died

in the twentieth century a silent death in the

existentialism that could only be disgusted with

the lies of modern violent mankind. For the old

existentialist J.P.

Sartre

(1905-1980),

who with his love for drugs and sex had lived

against Father Time with His classical morality,

it was too late to consult Freud to cure from

his Oedipus complex of having went against that

same father. Freud, before him, could solve the

problem himself neither by his speculations and

turn the tide of the philosophy of violence of

the class struggle that went further than that

of laborers against capitalists the way

Karl

Marx

(1818-1883) to the ideal had pictured it to

himself. We know that the national-socialistic

fascists of the freaked-out state-formalism and

-militarism are just as dangerous co-actors and

that finally there are the fundamentalists to

teach us once and for all a terrorist lesson for

being the arrogance of socialistic-fascistic

capitalism that considers poverty a sin...

For

us remains to be said that we at the beginning

of the twentieth century seriously have lost our

philosophical way. We don't, more or less

standardized, tick right, to the order of the

apparent sun; we are not in order with our

philosophies of morality, justice, economy and

time- management.

We in fact have lost the integrity of the

mindful and are hardly capable of staying

reasonable with the problems of cultural

integration, unemployment, the care for the

elderly and common heath-care. The

judicial-economic paradigm of controlling the

state with money and books of law is

compromised. The two sciences don't manage that

well alone being in power, the philosophers are

at their last gasp, the psychologists and

psychiatrists are constantly embarrassed

adapting dysfunctioning people to the ill-willed

system and the stock of gurus from the far east

is also depleted, for they have said and modeled

all they could. 'Please process your data, they

suffice', is their message. management.

We in fact have lost the integrity of the

mindful and are hardly capable of staying

reasonable with the problems of cultural

integration, unemployment, the care for the

elderly and common heath-care. The

judicial-economic paradigm of controlling the

state with money and books of law is

compromised. The two sciences don't manage that

well alone being in power, the philosophers are

at their last gasp, the psychologists and

psychiatrists are constantly embarrassed

adapting dysfunctioning people to the ill-willed

system and the stock of gurus from the far east

is also depleted, for they have said and modeled

all they could. 'Please process your data, they

suffice', is their message.

so

be it with with the chaos of post-modern time in

which even punk-hair and a leather jacket looks

bourgeois. We'll have to get our things back on

the road again and properly investigate to make

sure what exactly is holding us back. Is it

really so that we with A. Schopenhauer,

Madame

H. P. Blavatski

(1831-1891) and A.

Bailey

(1880-1949) know enough of eastern philosophy?

Is it really so that the rationalism of

Descartes would hold no value or sway anymore,

that the Hare Krishna's are a cult, that the

ether is nothing but the medium of the radio,

and that the empiricism of the English would be

so materialistic? Is it really so that the

liberal, the communist and the socialist,

nationalist be it idealist, offer no essential

contribution with the love for the natural

community-person? Is Einstein really our savior

to determine what is absolute in the universe?

No of course not. In fact is, filognostically

seen, the philosophy, or science for itself,

notwithstanding these questions, not the problem

at all. Philosophy, together with its empirical

result is, including theology and psychology,

the solution thus, but then with the restriction

of working like a good paradigm which combines

to the point of religion with a sane rational

spirituality and an empirical strategy of

respect for the person. No single truth of the

person is in fact wrong as long as that person

knows who he is, what his freedom to move,

emancipating or sliding down, would be and where

he stands in society.

Thus

may one, philosophically of opposition neither

contend that the ascending, inductive process of

acquiring knowledge, in India called aroha, of

the transcending or rising above,

moving from the particular to the general, would be

wrong because of the induction-problem that not

all swans are white. Religious people are, even

though for instance the Vishnu-adepts in India

are not in favor of it, doing nothing else when

they pray to realize themselves their Godhead,

making up half the world-population being

predominantly peaceful and sane with it. Neither

is the avaroha-process of the more scientific

deductive, rational and principally responsible

descending from the general to the specific of a

material distinction to be considered wrong.

Jesus, Mohammed, Krishna, you and also me thus

descended from heaven, even though our premiss

of divinity cannot be proven that states that

non-violence e.g. would be right with the

struggle that we on earth have to afford against

the evil of godlessness, illusion and injustice.

It is more an escher-staircase or a Jacob's

ladder to heaven we as well have to use walking

up as walking down (in fact doing both at the

same time).

from the particular to the general, would be

wrong because of the induction-problem that not

all swans are white. Religious people are, even

though for instance the Vishnu-adepts in India

are not in favor of it, doing nothing else when

they pray to realize themselves their Godhead,

making up half the world-population being

predominantly peaceful and sane with it. Neither

is the avaroha-process of the more scientific

deductive, rational and principally responsible

descending from the general to the specific of a

material distinction to be considered wrong.

Jesus, Mohammed, Krishna, you and also me thus

descended from heaven, even though our premiss

of divinity cannot be proven that states that

non-violence e.g. would be right with the

struggle that we on earth have to afford against

the evil of godlessness, illusion and injustice.

It is more an escher-staircase or a Jacob's

ladder to heaven we as well have to use walking

up as walking down (in fact doing both at the

same time).

No,

the problem is rather to arrive at an order, the

being in order, the fitting in with everyone in

one concept of world order. Everybody wants to

be in order, but nobody seems, as evidenced by

the continuation of warfare, the decay and other

miseries, to be really effective in the present

postmodern liberality, or to be in agreement, as

to how or what that order would be. Given the

desire to be effective and to know, we will have

to develop the love for the knowledge, the

filognosy, which pictures us that order

unambiguously. Also will we have to admit that

that will be of consequence and that thus

something like a reform, restoration, turnover

or rebirth must take place. The problem must be

identified, the solution must be offered, the

counter-arguments must be investigated, the

conclusion will have to be drawn and the summary

will have to be presented. In other words,

without this methodical approach it will all

result in nada; and therewith we end up with the

beginning of our general thesis concerning the

method as before was mentioned in the

introduction and the preface. With putting first

ancient India providing us the fundamental

notion of the method, the nyâya,

can one not escape the insight that we with our

modern philosophy of enlightenment concerning

individual responsibilities are but newcomers to

a classical teaching.  No

reason to be gloomy having lost Descartes out of

sight with our 'revolutions', now for our

atonement feeling abliged to sit at the feet of

the gurus from the East. We were, just

restarting as if our system was a computer, not

doing that bad at all. From Descartes we for a

great deal learned to know the Enlightenment of

an autonomous voice of reason from within

already. From him are we as persons defined as

selves of logic and reason. His writing is still

respected as the basis for the rationally

founded science to arrive from preconceived

premisses and principles at very concrete

practical propositions, implementations and

political decisions. As for this is the

filognosy concerned with the restoration of the

principle of the sovereignty of reason; and that

on the authority of the fact that we also find

that unambiguously with the for India most

important philosopher Dvaipâyana

Vyâsadeva, also named Bâdarayana,

who in the Krishna-bible, the Bhâgavata

Purâna 3.26:

62-70,

states that only by the power of reason the

original person can be awakened, and not by any

other case or godhead, not even by the supreme,

personal and purely good transcendental godhead

Lord Vishnu. He also in his famous Bhagavad

Gîtâ, 3.18,

provides evidence of this allegiance to the

sovereign interest, in stating that the pure

devotee is independent. It is that truth which

was overlooked in the modern chaos and with

which the rationalism of Descartes relativistic

with the modern electromagnetic time of

J.

C. Maxwell

(1831-1879) and Einstein seemed to have served

its turn at the one hand, while at the other

hand the church considered him a threat. But we

will, to the fundamental thesis of our

investigation, show that just this single vedic

truth of logic and reason on itself suffices,

despite of all the desperate western

philosophizing to our honor. The methodical

charter of order of Descartes is hereby valid as

the proof that we deliver to the defense of the

thesis that we as westerners ourselves are the

ones who constantly had the full rights of the

individual person and soul in his autonomy of

judgement in our banner. it was just the vedic

reference that was missing to be really sure

that we, be it more intuitive, have our roots in

the oldest and most traditional of human

culture. No

reason to be gloomy having lost Descartes out of

sight with our 'revolutions', now for our

atonement feeling abliged to sit at the feet of

the gurus from the East. We were, just

restarting as if our system was a computer, not

doing that bad at all. From Descartes we for a

great deal learned to know the Enlightenment of

an autonomous voice of reason from within

already. From him are we as persons defined as

selves of logic and reason. His writing is still

respected as the basis for the rationally

founded science to arrive from preconceived

premisses and principles at very concrete

practical propositions, implementations and

political decisions. As for this is the

filognosy concerned with the restoration of the

principle of the sovereignty of reason; and that

on the authority of the fact that we also find

that unambiguously with the for India most

important philosopher Dvaipâyana

Vyâsadeva, also named Bâdarayana,

who in the Krishna-bible, the Bhâgavata

Purâna 3.26:

62-70,

states that only by the power of reason the

original person can be awakened, and not by any

other case or godhead, not even by the supreme,

personal and purely good transcendental godhead

Lord Vishnu. He also in his famous Bhagavad

Gîtâ, 3.18,

provides evidence of this allegiance to the

sovereign interest, in stating that the pure

devotee is independent. It is that truth which

was overlooked in the modern chaos and with

which the rationalism of Descartes relativistic

with the modern electromagnetic time of

J.

C. Maxwell

(1831-1879) and Einstein seemed to have served

its turn at the one hand, while at the other

hand the church considered him a threat. But we

will, to the fundamental thesis of our

investigation, show that just this single vedic

truth of logic and reason on itself suffices,

despite of all the desperate western

philosophizing to our honor. The methodical

charter of order of Descartes is hereby valid as

the proof that we deliver to the defense of the

thesis that we as westerners ourselves are the

ones who constantly had the full rights of the

individual person and soul in his autonomy of

judgement in our banner. it was just the vedic

reference that was missing to be really sure

that we, be it more intuitive, have our roots in

the oldest and most traditional of human

culture.

The

Charter of Order for the purpose of reasoning

about the order of time and the control of

forces with the ether the way it is presented as

from now, is part of a philosophical treatise

that basically formulates our method of approach

with our filognostical love for knowledge. The

work it is taken from is called: 'On the

method'. It was written in the seventeenth

century by the french philosopher, who together

with the reason and the rationality defended the

concept of soul. Het is he who declared 'I think

therefore I am' to indicate that a sound mind on

itself is enough to be certain of one's

existence. Halfway this piece is the method

discussed that he discovered, but thus long

before him existed in India as a standard for

the central philosophy of also religiously

living together.

His

idea of the method consists of four parts to

which the Indian concept dividing the matter in

five, adds a preceding thesis. With him the

thesis is expressed in the first part of doubt.

His dividing accords with what in the

nyâya constitutes the

counter-argument in response to the doubt

before. Descartes' complexity is vedically then

the conclusion of the investigation and the

principle of completeness corresponds with what

in the nyâya is called the

siddhânta, the complete truth of

the end conclusion or the summary. Thus one

knows of Descartes:

1)

Doubt,

to be sure of what the truth would be.

2) Division,

in order to control the subject of study in

its different aspects.

3) Complexity,

or the assigning of such an order that the

relationships of the different elements of

the division becomes clear.

4) Completeness,

to cover with the order thus achieved the

complete of reality in such a manner that as

much elements as possible are

incorporated.

This

together constitutes the essence of the

classical philosophical method to uncover the

truth of, in our case, the subject of the order

of time and the consciousness of time in

checking us with the ether. The purpose of this

all is to arrive at a vision of our reality free

from illusion the way it is now, it was in the

past and will be in the future. It is the

striving for freedom from illusion which binds

philosophy, science and religion in one

unambiguous filognosy. Nor to the facts, nor to

the principles, nor to the person must we be of

illusion.

Later

in section III-A of this site, the department

Personal,

will René Descartes again be discussed.

But now first his treatise which, with his

verbose sentences, is not as easy to read must

be said. It is only a part of the entire

scripture, but that part which discusses the

essence of the method. This version is taken

from the, by us also upgraded, piece

free

available on the

internet,

and

was baptized: 'On Doubt, Division, Complexity

and Completeness':

'...I

was

then in Germany, attracted toward that place

by the wars in that country, which have not

yet been brought to a termination; and as I

was returning to the army from the coronation

of the emperor, the setting in of winter

arrested me in a locality where, as I found

no society to interest me, and was besides

fortunately undisturbed by any cares or

passions, I remained the whole day in

seclusion, with full opportunity to occupy my

attention with my own thoughts. Of these one

of the very first that occurred to me was,

that there is seldom so much perfection in

works composed of many separate parts, upon

which many had laid their hands, as in those

completed by a single master. Thus it is

observable that the buildings which a single

architect has planned and executed, are

generally more elegant and convenient than

those which several have attempted to

improve, by making old walls serve for

purposes for which they were not originally

built. Thus also, those ancient cities which,

from being at first only villages,  have

become, in course of time, large towns, are

usually but ill laid out compared with the

regularity constructed towns which a

professional architect has freely planned on

an open plain; so that although the several

buildings of the former may often equal or

surpass in beauty those of the latter, yet

when one observes their indiscriminate

juxtaposition, there a large one and here a

small, and the consequent crookedness and

irregularity of the streets, one is disposed

to allege that chance rather than any human

will guided by reason must have led to such

an arrangement. And if we consider that

nevertheless there have been at all times

certain officers whose duty it was to see

that private buildings contributed to public

ornament, the difficulty of reaching high

perfection with but the materials of others

to operate on, will be readily acknowledged.

In the same way I thought that those nations

which, starting from a semi-barbarous state

and advancing to civilization by slow

degrees, have had their laws successively

determined, and, as it were, forced upon them

simply by experience of the hurtfulness of

particular crimes and disputes, would by this

process come to be possessed of less perfect

institutions than those which, from the

commencement of their association as

communities, have followed the appointments

of some wise legislator. It is thus quite

certain that the constitution of the true

religion, the ordinances of which are have

become, in course of time, large towns, are

usually but ill laid out compared with the

regularity constructed towns which a

professional architect has freely planned on

an open plain; so that although the several

buildings of the former may often equal or

surpass in beauty those of the latter, yet

when one observes their indiscriminate

juxtaposition, there a large one and here a

small, and the consequent crookedness and

irregularity of the streets, one is disposed

to allege that chance rather than any human

will guided by reason must have led to such

an arrangement. And if we consider that

nevertheless there have been at all times

certain officers whose duty it was to see

that private buildings contributed to public

ornament, the difficulty of reaching high

perfection with but the materials of others

to operate on, will be readily acknowledged.

In the same way I thought that those nations

which, starting from a semi-barbarous state

and advancing to civilization by slow

degrees, have had their laws successively

determined, and, as it were, forced upon them

simply by experience of the hurtfulness of

particular crimes and disputes, would by this

process come to be possessed of less perfect

institutions than those which, from the

commencement of their association as

communities, have followed the appointments

of some wise legislator. It is thus quite

certain that the constitution of the true

religion, the ordinances of which are

derived

from God, must be incomparably superior to

that of every other. And, to speak of human

affairs, I believe that the supremacy of

Sparta was due not to the goodness of each of

its laws in particular, for many of these

were very strange, and even opposed to good

morals, but to the circumstance that,

originated by a single individual, they all

tended to a single end. In the same way I

thought that the sciences contained in books

(such of them at least as are made up of

probable reasonings, without demonstrations),

composed as they are of the opinions of many

different individuals massed together, are

farther removed from truth than the simple

inferences which a man of good sense using

his natural and unprejudiced judgment draws

respecting the matters of his experience. And

because we have all to pass through a state

of infancy to manhood, and have been of

necessity, for a length of time, governed by

our desires and preceptors (whose dictates

were frequently conflicting, while neither

perhaps always counseled us for the best), I

farther concluded that it is almost

impossible that our judgments can be so

correct or solid as they would have been, had

our reason been mature from the moment of our

birth, and had we always been guided by it

alone. derived

from God, must be incomparably superior to

that of every other. And, to speak of human

affairs, I believe that the supremacy of

Sparta was due not to the goodness of each of

its laws in particular, for many of these

were very strange, and even opposed to good

morals, but to the circumstance that,

originated by a single individual, they all

tended to a single end. In the same way I

thought that the sciences contained in books

(such of them at least as are made up of

probable reasonings, without demonstrations),

composed as they are of the opinions of many

different individuals massed together, are

farther removed from truth than the simple

inferences which a man of good sense using

his natural and unprejudiced judgment draws

respecting the matters of his experience. And

because we have all to pass through a state

of infancy to manhood, and have been of

necessity, for a length of time, governed by

our desires and preceptors (whose dictates

were frequently conflicting, while neither

perhaps always counseled us for the best), I

farther concluded that it is almost

impossible that our judgments can be so

correct or solid as they would have been, had

our reason been mature from the moment of our

birth, and had we always been guided by it

alone.

It

is true, however, that it is not customary to

pull down all the houses of a town with the

single design of rebuilding them differently,

and thereby rendering the streets more

handsome; but it often happens that a private

individual takes down his own with the view

of erecting it anew, and that people are even

sometimes constrained to this when their

houses are in danger of falling from age, or

when the foundations are insecure. With this

before me by way of example, I was persuaded

that it would indeed be preposterous for a

private individual to think of reforming a

state by fundamentally changing it in every

respect, and overturning it in order to set

it up amended; and the same I thought was

true of any similar project for reforming the

body of the sciences, or the order of

teaching them established in the schools: but

as for the opinions which up to that time I

had embraced, I thought that I could not do

better than resolve at once to sweep them

wholly away, that I might afterwards be in a

position to admit either others more correct,

or even perhaps the same when they had

undergone the scrutiny of reason. I firmly

believed that in this way I should much

better succeed in the conduct of my life,

than if I built only upon old foundations,

and leaned upon principles which, in my

youth, I had taken upon trust. For although I

recognized various difficulties in this

undertaking, these were not, however, without

remedy, nor once to be compared with such as

attend the slightest reformation in public

affairs. Large bodies, if once overthrown,

are with great difficulty set up again, or

even kept erect when once seriously shaken,

and

the fall of such is always disastrous. Then

if there are any imperfections in the

constitutions of states (and that many such

exist the diversity of constitutions is alone

sufficient to assure us), custom has without

doubt materially dealt successfully with

their inconveniences, and has even managed to

steer altogether clear of, or insensibly

corrected a number which keen discernment

could not have provided against with equal

effect; and, in fine, the defects are almost

always more tolerable than the change

necessary for their removal; in the same

manner that highways which wind among

mountains, by being much frequented, become

gradually so smooth and convenient, that it

is much better to follow them than to seek a

straighter path by climbing over the tops of

rocks and descending to the bottoms of

precipices. and

the fall of such is always disastrous. Then

if there are any imperfections in the

constitutions of states (and that many such

exist the diversity of constitutions is alone

sufficient to assure us), custom has without

doubt materially dealt successfully with

their inconveniences, and has even managed to

steer altogether clear of, or insensibly

corrected a number which keen discernment

could not have provided against with equal

effect; and, in fine, the defects are almost

always more tolerable than the change

necessary for their removal; in the same

manner that highways which wind among

mountains, by being much frequented, become

gradually so smooth and convenient, that it

is much better to follow them than to seek a

straighter path by climbing over the tops of

rocks and descending to the bottoms of

precipices.

Hence

it is that I cannot in any degree approve of

those restless and prying who, called neither

by birth nor fortune to take part in the

management of public affairs, are yet always

projecting reforms; and if I thought that

this tract contained aught which might

justify the suspicion that I was a victim of

such folly, I would by no means permit its

publication. I have never contemplated

anything higher than the reformation of my

own opinions, and basing them on a foundation

wholly my own. And although my own

satisfaction with my work has led me to

present here a draft of it, I do not by any

means therefore recommend to every one else

to make a similar attempt. Those whom God has

endowed with a larger measure of genius will

entertain, perhaps, designs still more

exalted; but for the many I am much afraid

lest even the present undertaking be more

than they can safely venture to imitate.

The

single design to strip one's self of all past

beliefs is one that ought not to be taken by

every one. The majority of men is composed of

two classes, for neither of which would this

be at all a befitting resolution: in the

first place, of those who with more than a

due confidence in their own powers, are rash

in their judgments and want the patience

requisite for orderly and circumspect

thinking; whence it happens, that if men of

this class once take the liberty to doubt of

their accustomed opinions, and quit the

beaten highway, they will never be able to

thread the byway that would lead them by a

shorter course, and will lose themselves and

continue to wander for life; in the second

place, of those who, possessed of sufficient

sense or modesty to determine that there are

others who excel them in the power of

discriminating between truth and error, and

by whom they may be instructed, ought rather

to content themselves with the opinions of

such than trust for more correct to their own

reason. The

single design to strip one's self of all past

beliefs is one that ought not to be taken by

every one. The majority of men is composed of

two classes, for neither of which would this

be at all a befitting resolution: in the

first place, of those who with more than a

due confidence in their own powers, are rash

in their judgments and want the patience

requisite for orderly and circumspect

thinking; whence it happens, that if men of

this class once take the liberty to doubt of

their accustomed opinions, and quit the

beaten highway, they will never be able to

thread the byway that would lead them by a

shorter course, and will lose themselves and

continue to wander for life; in the second

place, of those who, possessed of sufficient

sense or modesty to determine that there are

others who excel them in the power of

discriminating between truth and error, and

by whom they may be instructed, ought rather

to content themselves with the opinions of

such than trust for more correct to their own

reason.

For

my own part, I should doubtless have belonged

to the latter class, had I received

instruction from but one master, or had I

never known the diversities of opinion that

from time immemorial have prevailed among men

of the greatest learning. But I had become

aware, even so early as during my college

life, that no opinion, however absurd and

incredible, can be imagined, which has not

been maintained by some one of the

philosophers; and afterwards in the course of

my travels I remarked that all those whose

opinions are decidedly unacceptable to ours

are not in that account barbarians and

savages, but on the contrary that many of

these nations make an equally good, if not

better, use of their reason than we do. I

took into account also the very different

character which a person brought up from

infancy in France or Germany exhibits, from

that which, with the same mind originally,

this individual would have possessed had

he

lived always among the Chinese or with

savages, and the circumstance that in dress

itself the fashion which pleased us ten years

ago, and which may again, perhaps, be

received into favor before ten years have

gone, appears to us at this moment

extravagant and ridiculous. I was thus led to

infer that the ground of our opinions is far

more custom and example than any certain

knowledge. And, finally, although such be the

ground of our opinions, I remarked that a

plurality of voices is no guarantee of truth

where it is at all of difficult discovery, as

in such cases it is much more likely that it

will be found by one than by many. I could,

however, select from the crowd no one whose

opinions seemed worthy of preference, and

thus I found myself constrained, as it were,

to use my own reason in the conduct of my

life. he

lived always among the Chinese or with

savages, and the circumstance that in dress

itself the fashion which pleased us ten years

ago, and which may again, perhaps, be

received into favor before ten years have

gone, appears to us at this moment

extravagant and ridiculous. I was thus led to

infer that the ground of our opinions is far

more custom and example than any certain

knowledge. And, finally, although such be the

ground of our opinions, I remarked that a

plurality of voices is no guarantee of truth

where it is at all of difficult discovery, as

in such cases it is much more likely that it

will be found by one than by many. I could,

however, select from the crowd no one whose

opinions seemed worthy of preference, and

thus I found myself constrained, as it were,

to use my own reason in the conduct of my

life.

But

like one walking alone and in the dark, I

resolved to proceed so slowly and with such

wary, that if I did not advance far, I would

at least guard against falling. I did not

even choose to dismiss summarily any of the

opinions that had crept into my belief

without having been introduced by reason, but

first of all took sufficient time carefully

to satisfy myself of the general nature of

the task I was setting myself, and ascertain

the true method by which to arrive at the

knowledge of whatever lay within the compass

of my powers.

Among

the branches of philosophy, I had, at an

earlier period, given some attention to

logic, and among those of the mathematics to

geometrical analysis and algebra, -- three

arts or sciences which ought, as I conceived,

to contribute something to my design. But, on

examination, I found that, as for logic, its

syllogisms and the majority of its other

precepts are of avail - rather in the

communication of what we already know, or

even as the art of Lully, in speaking without

judgment of things of which we are ignorant,

than in the investigation of the unknown; and

although this science contains indeed a

number of correct and very excellent

precepts, there are, nevertheless, so many

others, and these either injurious or

superfluous, mingled with the former, that it

is almost quite as difficult to effect a

severance of the true from the false as it is

to extract a Diana or a Minerva from a rough

block of marble. Then as to the analysis of

the ancients and the algebra of the moderns,

besides that they embrace only matters highly

abstract, and, to appearance, of no use, the

former is so exclusively restricted to the

consideration of figures, that it can

exercise  the

understanding only on condition of greatly

fatiguing the imagination; and, in the

latter, there is so complete a subjection to

certain rules and formulas, that there

results an art full of confusion and

obscurity calculated to embarrass, instead of

a science fitted to cultivate the mind. By

these considerations I was induced to seek

some other method which would comprise the

advantages of the three and be exempt from

their defects. And as a multitude of laws

often only hinders justice, so that a state

is best governed when, with few laws, these

are rigidly administered; in like manner,

instead of the great number of precepts of

which logic is composed, I believed that the

four following would prove perfectly

sufficient for me, provided I took the firm

and unwavering resolution never in a single

instance to fail in observing

them. the

understanding only on condition of greatly

fatiguing the imagination; and, in the

latter, there is so complete a subjection to

certain rules and formulas, that there

results an art full of confusion and

obscurity calculated to embarrass, instead of

a science fitted to cultivate the mind. By

these considerations I was induced to seek

some other method which would comprise the

advantages of the three and be exempt from

their defects. And as a multitude of laws

often only hinders justice, so that a state

is best governed when, with few laws, these

are rigidly administered; in like manner,

instead of the great number of precepts of

which logic is composed, I believed that the

four following would prove perfectly

sufficient for me, provided I took the firm

and unwavering resolution never in a single

instance to fail in observing

them.

The first

was

never to accept anything for true which I

did not clearly know to be

such;

that is to say, carefully to avoid

precipitancy and prejudice, and to

comprise nothing more in my judgement than

what was presented to my mind so clearly

and distinctly as to exclude all ground of

doubt.

The first

was

never to accept anything for true which I

did not clearly know to be

such;

that is to say, carefully to avoid

precipitancy and prejudice, and to

comprise nothing more in my judgement than

what was presented to my mind so clearly

and distinctly as to exclude all ground of

doubt.

The second,

to

divide each of the difficulties under

examination into as many parts as

possible, and as might be necessary for

its adequate

solution.

The second,

to

divide each of the difficulties under

examination into as many parts as

possible, and as might be necessary for

its adequate

solution.

The third, to conduct my thoughts

in

such order

that,

by commencing with objects the simplest

and easiest to know,

I

might ascend by little and little, and, as

it were, step by step, to the knowledge of

the more

complex;

assigning in thought a certain order even

to those objects which in their own nature

do not stand in a relation of antecedence

and sequence.

The third, to conduct my thoughts

in

such order

that,

by commencing with objects the simplest

and easiest to know,

I

might ascend by little and little, and, as

it were, step by step, to the knowledge of

the more

complex;

assigning in thought a certain order even

to those objects which in their own nature

do not stand in a relation of antecedence

and sequence.

And fourth,

in

every case to make enumerations so

complete, and reviews so general, that I

might be assured that nothing was

omitted.

And fourth,

in

every case to make enumerations so

complete, and reviews so general, that I

might be assured that nothing was

omitted.

The

long chains of simple and easy reasonings by

means of which geometers are accustomed to

reach the conclusions of their most difficult

demonstrations, had led me to imagine that

all things, to the knowledge of which man is

competent, are mutually connected in the same

way, and that there is nothing so far removed

from us as to be beyond our reach, or so

hidden that we cannot discover it, provided

only we abstain from accepting the false for

the true, and always preserve in our thoughts

the order necessary for the deduction of one truth from

another. And I had little difficulty in

determining the objects with which it was

necessary to commence, for I was already

persuaded that it must be with the simplest

and easiest to know, and, considering that of

all those who have hitherto sought truth in

the sciences, the mathematicians alone have

been able to find any demonstrations, that

is, any certain and evident reasons, I did

not doubt but that such must have been the

rule of their investigations. I resolved to

commence, therefore, with the examination of

the simplest objects, not anticipating,

however, from this any other advantage than

that to be found in accustoming my mind to

the love and nourishment of truth, and to a

distaste for all such reasonings as were

unsound. But I had no intention on that

account of attempting to master all the

particular sciences commonly denominated

mathematics: but observing that, however

different their objects, they all agree in

considering only the various relations or

proportions subsisting among those objects, I

thought it best for my purpose to consider

these proportions in the most general form

possible, without referring them to any

objects in particular, except such as would

most facilitate the knowledge of them, and

without by any means restricting them to

these, that afterwards I might thus be the

better able to apply them to every other

class of objects to which they are

legitimately applicable. Perceiving further,

that in order to understand these relations I

should

necessary for the deduction of one truth from

another. And I had little difficulty in

determining the objects with which it was

necessary to commence, for I was already

persuaded that it must be with the simplest

and easiest to know, and, considering that of

all those who have hitherto sought truth in

the sciences, the mathematicians alone have

been able to find any demonstrations, that

is, any certain and evident reasons, I did

not doubt but that such must have been the

rule of their investigations. I resolved to

commence, therefore, with the examination of

the simplest objects, not anticipating,

however, from this any other advantage than

that to be found in accustoming my mind to

the love and nourishment of truth, and to a

distaste for all such reasonings as were

unsound. But I had no intention on that

account of attempting to master all the

particular sciences commonly denominated

mathematics: but observing that, however

different their objects, they all agree in

considering only the various relations or

proportions subsisting among those objects, I

thought it best for my purpose to consider

these proportions in the most general form

possible, without referring them to any

objects in particular, except such as would

most facilitate the knowledge of them, and

without by any means restricting them to

these, that afterwards I might thus be the

better able to apply them to every other

class of objects to which they are

legitimately applicable. Perceiving further,

that in order to understand these relations I

should  sometimes

have to consider them one by one and

sometimes only to bear them in mind, or

embrace them in the totality, I thought that,

in order the better to consider them

individually, I should view them as

subsisting between straight lines, than which

I could find no objects more simple, or

capable of being more distinctly represented

to my imagination and senses; and on the

other hand, that in order to retain them in

the memory or embrace an aggregate of many, I

should express them by certain characters the

briefest possible. In this way I believed

that I could borrow all that was best both in

geometrical analysis and in algebra, and

correct all the defects of the one by help of

the other. sometimes

have to consider them one by one and

sometimes only to bear them in mind, or

embrace them in the totality, I thought that,

in order the better to consider them

individually, I should view them as

subsisting between straight lines, than which

I could find no objects more simple, or

capable of being more distinctly represented

to my imagination and senses; and on the

other hand, that in order to retain them in

the memory or embrace an aggregate of many, I

should express them by certain characters the

briefest possible. In this way I believed

that I could borrow all that was best both in

geometrical analysis and in algebra, and

correct all the defects of the one by help of

the other.

And,

in point of fact, the accurate observance of

these few precepts gave me, I take the

liberty of saying, such ease in unraveling

all the questions embraced in these two

sciences, that in the two or three months I

devoted to their examination, not only did I

reach solutions of questions I had formerly

deemed exceedingly difficult but even as

regards questions of the solution of which I

continued ignorant;  I

was enabled, as it appeared to me, to

determine the means whereby, and the extent

to which a solution was possible; results

attributable to the circumstance that I

commenced with the simplest and most general

truths, and that thus each truth discovered

was a rule available in the discovery of

subsequent ones. Nor in this perhaps shall I

appear too vain, if it be considered that, as

the truth on any particular point is one,

whoever apprehends the truth, knows all that

on that point can be known. The child, for

example, who has been instructed in the

elements of arithmetic, and has made a

particular addition, according to rule, may

be assured that he has found, with respect to

the sum of the numbers before him, and that

in this instance is within the reach of human

genius. Now, in conclusion, the method which

teaches adherence to the true order, and an

exact enumeration of all the conditions of

the thing sought includes all that gives

certitude to the rules of

arithmetic. I

was enabled, as it appeared to me, to

determine the means whereby, and the extent

to which a solution was possible; results

attributable to the circumstance that I

commenced with the simplest and most general

truths, and that thus each truth discovered

was a rule available in the discovery of

subsequent ones. Nor in this perhaps shall I

appear too vain, if it be considered that, as

the truth on any particular point is one,

whoever apprehends the truth, knows all that

on that point can be known. The child, for

example, who has been instructed in the

elements of arithmetic, and has made a

particular addition, according to rule, may

be assured that he has found, with respect to

the sum of the numbers before him, and that

in this instance is within the reach of human

genius. Now, in conclusion, the method which

teaches adherence to the true order, and an

exact enumeration of all the conditions of

the thing sought includes all that gives

certitude to the rules of

arithmetic.

But

the chief ground of my satisfaction with this

method, was the assurance I had of thereby

exercising my reason in all matters, if not

with absolute perfection, at least with the

greatest attainable by me: besides, I was

conscious that by its use my mind was

becoming gradually habituated to clearer and

more distinct conceptions of its objects; and

I hoped also, from not having restricted this

method to any particular matter, to apply it

to the difficulties of the other sciences,

with not less success than to those of

algebra. I should not, however, on this

account have ventured at once on the

examination of all the difficulties of the

sciences which presented themselves to me,

for this would have been contrary to the

order prescribed in the method, but observing

that the knowledge of such is dependent on

principles borrowed from philosophy, in which

I found nothing certain, I thought

it necessary first of all to endeavor to

establish its principles. And

because I observed, besides, that an inquiry

of this kind was of all others of the

greatest moment, and one in which rashness

and anticipation in judgment were most to be

dreaded, I thought that I ought not to

approach it till I had reached a more mature

age (being at that time but twenty-three),

and had first of all employed much of my time

in preparation for the work, as well by

eradicating from my mind all the erroneous

opinions I had up to that moment accepted, as

by amassing variety of experience to afford

materials for my reasonings, and by

continually exercising myself in my chosen

method with a view to increased skill in its

application.'

Thus

far René Descartes on the method. It is

this method which, departing from the true

religion of the sane mind of tolerance and

prudence, from single-minded witnessing through

doubt arrives at a clearly to oversee science

incorporating each and everyone. That

mathematically correct deduction from the

necessary and inevitable order which

non-repressively departs from a certain

conceptual simplicity, ultimately has brought us

the power of reforming the reason with which we

first of all created this website and we

ourselves - not only literary operating thus -

have found a life. Not to say that rationalism

would be our final belief, or that we for that

reason would want to philosophize endlessly

about the multitude of philosophers* also

commenting on this subject, but because the

method as such reflects the expression in our

western terms of a truth, as Descartes says a

truth of principles, which we find presented in

the oldest scriptures of India. We, according

our fundamental thesis, want to demonstrate with

it, that concerning the time and the order

thereof with the ether, of which Descartes said

that the universe is purely made of it, it in

the foregoing cultures in the world is the way

the dutch philosopher and ethical thinker Baruch

Spinoza filognostically correctly stated it:

'Still

can the greater of nature not be denied and

retains she her fixed and immutable

order'.

For

more info on the person of this philosopher and

his works and place in history go to the

renown

ego's page

*

See the timelinks-page

and the quotes-page

for more philosophers about time.

*

For more info on this philosopher and his works

and place in history, see

the

Renown

Ego's - page.

*

See for an

overview

of the history of philosophy Bryan Magee's

highly readable

book

'The

Story of

Philosophy'

(1998,

Dorling Kinserly Limited London).

*

Other philosophy-links: the Linking-Library

- philosophy.

versie

in het

Nederlands

|

|